Science has yet to invent a device that can read your mind. But that day is coming, and it’s a lot closer than you might think.

Using galvanic skin response sensors, electroencephalographs, and cameras that track eye movement and record facial expressions, brain researchers already believe they can tell when you’re fascinated or bored, confused or excited, angry or serene.

(“A Clockwork Orange” — IMDB)

While the technology is far from flawless, it’s good enough for companies like Procter & Gamble, universities like Harvard and Stanford, and branches of the U.S. military to pour millions into wiring people up and trying to find out what’s really going on inside their noggins.

Now the small but rapidly growing neurotech industry wants to use these tools to help make our kids smarter. By combining brain measurement with educational games, they hope to identify the barriers to learning and automatically overcome them.

It’s an audacious idea with huge potential, even if its effectiveness is still in question. And the challenges – from parental acceptance to privacy concerns – are daunting.

No brain, no gain

Not so long ago, electroencephalographs costs tens of thousands of dollars. Now you can buy a simple consumer-grade EEG headset from companies like Emotiv, InteraXon, or NeuroSky for $100 to $500; these gadgets not only measure your brain waves but can be used as control devices, to manipulate objects on a computer screen.

The $500 EPOC+ collects 14 different signals from your brain, measures your facial expressions, and let you control apps with your mind. (Emotive)

For example, Crooked Tree Studios’ “Throw Trucks With Your Mind”video game uses an inexpensive NeuroSky headset; you pick up vehicles and hurl them simply by concentrating. With Uncle Milton’s “Star Wars: The Force Trainer II” toy, you don a headset and try to raise a holographic X-Wing Fighter out of a swamp. InteraXon just released version 2.0 of its Muse headset and mobile app, which trains you to relax your mind via a series of guided meditation exercises.

The question is, can the same technology that allows you to chuck trucks and levitate spacecraft improve your child’s math scores?

In December, Southern California start-up Qneuro plans to release the first in a series of titles that rely on brain wave recording to identify where kids in grades K-6 are in their optimal learning state.

Its first title, a math game called Axon Infinity: Space Academy, uses a commercial EEG headset to measure “cognitive load” — essentially how hard a student’s brain is working. It then adjusts what the player experiences to optimize conditions for learning by, say, altering the game’s visual complexity, says CEO Dhiraj Jeyanandarajan, a neurophysiologist by training. When the cognitive load is optimal, the child’s ability to learn the material increases, he says.

A scene from Axon Infinity: Space Academy. (Qneuro)

Because every child’s brain is unique, the game would adjust itself differently for each student – creating a kind of individualized lesson plan at the brain wave level. So far, testing has been limited but encouraging, Jeyanandarajan adds. Students who play the game with the neural feedback system show faster mastery of basic concepts than those who don’t, he claims.

I can feel it, Dave

The question companies like these are trying to answer is if it’s possible to teach a computer how to recognize whether a student is engaged or frustrated and then respond as a human teacher might, says Robert Christopherson, who is pursuing a PhD in educational technology from Arizona State University.

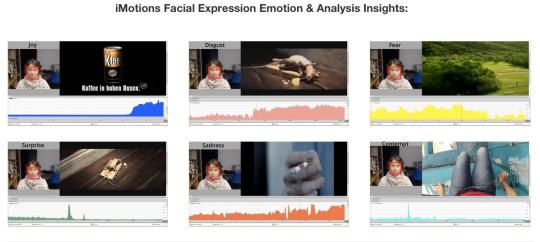

Christopherson’s day job is as training and support specialist at iMotions, which makes software that allows companies like P&G and Kraft Foods to take input from a range of psycho-physiological or biometric sensors and sync them to actual events in real time.

iMotion’s biometrics research platform can identify basic emotional states by analyzing facial expressions. (iMotions)

“In a classroom a teacher can see that a student is disengaged and provide a quick response,” he says. “An online learning environment is like having a teacher who can’t see or hear emotion. Essentially, we’re trying to teach computers empathy.”

At the same time, these systems can also help human teachers identify when a student is struggling and intervene more quickly, says Christopherson.

“In 10 years there will be so many sensors in the classroom that, before you even have a question, the teacher will be like, ‘I know you’ve been struggling with this, John, here’s the answer to the question you’re going to have in three minutes.'”

The quantified kid

By building a model of how each student learns, you can enable her to master topics in a fraction of the time it might otherwise require. But it also threatens the last bastion of personal privacy – what happens inside her own skull.

“Every action a learner takes refines the model a system has of them, making it almost as easy to identity you as with your own fingerprint,” says Christopherson. “Even if I don’t know your name, I can tell where you’re going to school and how you’re doing in math, and as soon as you pop up on the grid I can probably identify who you are. It’s a huge issue.”

Concerns like these have led to the formation of the Center for Responsible Brainwave Technologies (CeReB), an industry group whose goal is to promote the use of neuro technology “in a safe, ethical, and socially responsible manner,” according to the group’s Web site.

Ariel Garten, CEO of InteraXon, wearing her company’s Muse headset. (InteraXon)

In a conversation at the NeuroGaming Conference in San Francisco last week, the group’s chairperson, InteraXon CEO Ariel Garten, told me she was confident CeReB will be able to identify and expose any bad actors who are abusing brain data for their own purposes.

“Our philosophy is that your brain data is your brain data – you own it and you can say what happens to it,” says Garten.

“The brain wave community is fairly small and we know just about everyone in it,” she adds. “If someone misbehaves, we’ll know about it and so will everyone else.”

Establishing ethical and privacy guidelines for brain-computer interactions is the easy part. Ensuring that everyone plays by the rules is much harder — especially when some of the biggest players in this field are marketers who seek to gauge the potential success of products before they’re launched. And other industry attempts at self-regulation — like Web advertisers and Internet privacy — have had mixed success at best.

The potential for technology to create truly personalized learning experiences for kids and adults alike is exciting. But it’s a thing we need to enter into with our eyes wide open.

No comments:

Post a Comment